Kwame Nkrumah may have died and been buried many years ago but the recurrence in the telling of stories surrounding him are testament of one undeniable, almost unquantifiable proof that he was not ordinary.

The man was a legend who placed Ghana on the path that has led it to where it is today.

And the story about how he was displaced from his constitutional position as Ghana’s president is very much a well-known public information, but have you thought carefully about the engineers of that plot and the people who, literally, opened up Nkrumah’s chest of skeletons for his opposers to capitalise on?

Well, in this GhanaWeb article, we reflect on the names and the personalities of the people who betrayed Kwame Nkrumah; people who were mostly very close to the country’s first president.

Their names and the brief details about what they did in support of the coup plotters who got Nkrumah ousted have been teased from a video shared on YouTube by Talking Africa. Here they are, in no particular order:

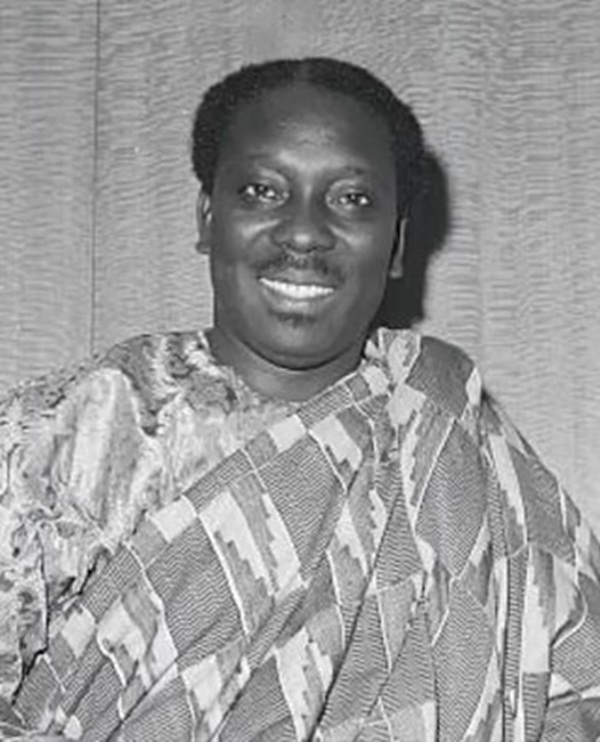

Alex Quayson-Sackey, Nkrumah’s Minister of Foreign Affairs

He was appointed Ghana’s Minister of Foreign Affairs by Osagyefo Dr Kwame Nkrumah in 1965 and remained in this position until the coup that deposed the Nkrumah government on February 24, 1966.

Right after the coup, Quayson-Sackey returned to Accra and pledged his loyalty to the men who had illegally seized power. This happened only days after the coup. At the time, Quayson-Sackey was supposed to be in Addis Ababa, not Accra.

That was the agreement he had with Nkrumah.

To fully understand the situation, it is worth stating that Dr Kwame Nkrumah was on his way to Hanoi, Vietnam, at the invitation of President Ho Chi Minh as the Vietnam War was ongoing, and Nkrumah had been invited to help mediate peace.

The plane carrying Nkrumah and his entourage had barely reached Beijing — then called Peking — when the coup was carried out in Ghana. The plotters deliberately waited until he was far from the country before striking.

Nkrumah later described the situation in these words:

“The cowards who seized power by force of arms behind my back knew they did not have the support of the people of Ghana and therefore thought it wise to wait until I was not only out of the country but well beyond the range of a quick return.”

Upon his arrival in China, Nkrumah was officially informed of the coup by Chinese leaders. There was uncertainty surrounding his next move, with conflicting reports suggesting he might return immediately to Accra.

Nkrumah’s first instinct was indeed to return to Ghana at once. However, this proved impractical. The Ghana Airways VC10 aircraft he had used was left behind in Myanmar, and he believed it was vital to return within 24 hours of the coup but at the time, the flight duration from Beijing to Accra made this impossible.

As a result, Nkrumah issued a public statement asserting that he remained the constitutional Head of State of Ghana and called on the army to return to their barracks. He then discussed developments in Ghana with officials in his entourage. Their reaction, however, alarmed him.

Instead of displaying courage, many of them were frightened.

According to Nkrumah, Alex Quayson-Sackey developed severe diarrhoea and reportedly visited the lavatory about twenty times that day. While everyone was understandably anxious about the safety of their families, Nkrumah observed that many officials were also preoccupied with their bank accounts and properties.

As he put it, “A man’s heart lies where his treasure is.” Even allowing for the fact that they had more to lose than others, he found it difficult to understand how easily they lost their composure. It was as though they had surrendered at the first sign of danger.

Nevertheless, they managed to regain enough composure for Nkrumah to discuss his next steps with them. These plans included assigning Alex Quayson-Sackey an important mission.

As foreign minister, he was to travel to Addis Ababa to represent the legitimate Ghanaian government at an upcoming OAU Foreign Ministers’ Conference.

That mission, however, was never carried out. Instead of going to Addis Ababa, Quayson-Sackey flew first to London and then on to Accra.

Nkrumah later described this act as a betrayal.

“Instead of rising to the occasion and accepting this great challenge and responsibility, he went to Accra and offered his services to the new colonialist puppets, the so-called National Liberation Council. The latter, it seems, made little use of him. Traitors have no friends,” he said.

In a later interview, Quayson-Sackey explained his actions.

He said he returned to Ghana because he had been dismissed, all ministers had been detained, and he believed it was necessary to submit himself to the new government.

He repeated his claim that upon his arrival, he sensed a fresh wave of change in the country.

He argued that there had been pent-up frustrations among the population for years, driven by the high cost of living, shortages of goods, and rising food prices. Having returned to Ghana in November after eleven years abroad to take up the role of foreign minister, he said he could sense widespread discontent.

Parliamentary debates, particularly criticism of the Minister of Agriculture, convinced him that serious upheaval was inevitable, but this is the same man Nkrumah had appointed Ghana’s Ambassador and Permanent Representative to the United Nations from 1959 to 1965, making him the first Black African to serve as President of the UN General Assembly between 1964 and 1965. He also served as Ghana’s ambassador to Cuba and Mexico during that period.

Yet, despite his prominent roles, he had no hesitation in pledging loyalty to the coup makers. Critics have said that if he genuinely believed the Nkrumah government was leading the country into crisis, why did he not resign from office before February 24, 1966?

J E Bossman, Ghana’s High Commissioner to the UK

J E Bossman, one of the men who quickly defected after the overthrow of Kwame Nkrumah, is one of several early nationalists figures whose relationship with Nkrumah deteriorated during the consolidation of power by the Convention People’s Party (CPP) after independence.

Like others from that era, his story is often told through partisan lenses, especially by CPP loyalists who equated dissent with betrayal.

After the coup, he defected and quickly declared his unqualified support for the coup plotters.

Fred Arkhurst, Ghana’s Permanent Representative to the UN

Fred Arkhurst, who had replaced Quayson-Sackey as Ghana’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations, was also one of the people who quickly turned their backs on Nkrumah.

Fred Arkhurst (often referred to in Ghanaian political history as Frederick Grant Bantama Arkhurst) was an early associate of Dr Kwame Nkrumah and a member of the Convention People’s Party (CPP) during the formative years of Ghana’s independence struggle.

His later political choices, however, placed him among figures Nkrumah and the CPP regarded as traitors or defectors.

Like many early CPP figures, he benefited from the party’s mass support and revolutionary appeal in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

After leaving the CPP, Arkhurst aligned himself with opposition forces, which were later associated with the National Liberation Movement (NLM) and the United Party (UP) tradition.

From Nkrumah’s perspective, this was not merely dissent but active collaboration with forces seen as working against the nationalist project.

Eric Otoo, a senior civil servant entrusted with national security while Nkrumah was abroad

Eric Otoo reportedly provided critical information to the coup plotters. Nkrumah later remarked that without Otoo’s cooperation, the coup might not have succeeded.

Eric Otoo appears in accounts of early CPP politics as one of the figures who fell out with Kwame Nkrumah during the turbulent years after independence. Unlike more prominent defectors, Otoo is less extensively documented, which has allowed politics and memory to shape how his role is described.

Otoo later became critical of Nkrumah’s governance, particularly the suppression of internal dissent within the CPP, the Preventive Detention Act (PDA), and the gradual transformation of Ghana into a de facto one-party state.

His disagreements reportedly led to a break with the CPP leadership, placing him on the opposite side of Nkrumah politically.

After leaving the CPP fold, Otoo aligned himself — directly or indirectly — with anti-Nkrumah political forces, both at home and abroad.

Komla Agbeli Gbedemah, Nkrumah’s Minister of Finance

Long before all these events, another profound betrayal had already taken shape. This involved Nkrumah’s longtime friend and Finance Minister K A Gbedemah.

Though instrumental in the CPP’s early successes and a key figure in government, Gbedemah’s conservative economic views and pro-Western stance increasingly clashed with Nkrumah’s vision.

By 1961, tensions had escalated. After disputes over economic policy and the creation of a budget bureau under the presidency, Gbedemah was moved from finance to health.

Around the same time, investigations into corruption among ministers led to forced resignations, including Gbedemah’s.

Declassified US documents later revealed that even before his resignation, Gbedemah had contemplated overthrowing Nkrumah and sought American support. Though those plans failed, he continued efforts abroad to undermine the government.

There were other names such as Enoch Okoh, Head of Ghana’s Civil Service; and Michael Dei-Anang, Ambassador Extraordinary in charge of the African Affairs Secretariat.

There was also Kwesi Armah, Minister of Foreign Trade, who had left Nkrumah in Moscow to attend to what they described as urgent private matters and promised to return so that they will travel together with Nkrumah to Conakry, Guinea, never returned.

They also effectively defected.

Watch the full video below:

AE