Editor’s Note: A version of this story appeared in CNN’s Meanwhile in China newsletter, a three-times-a-week update exploring what you need to know about the country’s rise and how it impacts the world. Sign up here.

Hong Kong

CNN

—

2022 is finally here. And for China, there’s no shortage of big moments on the horizon – from the Beijing Winter Olympics to the 20th Communist Party Congress in the fall.

The stakes are undoubtedly high, but success is by no means guaranteed. And numerous questions abound.

As the coronavirus pandemic drags into its third year, will China remain isolated from the rest of the world?

Will President Xi Jinping secure a third term in power as widely expected – and will that result in a further tightening of control? And just how far is a newly emboldened Xi willing to go?

What about China’s place on the world stage? Will we see a further deterioration in Beijing’s relations with the West?

Here are five key things to watch in China this year.

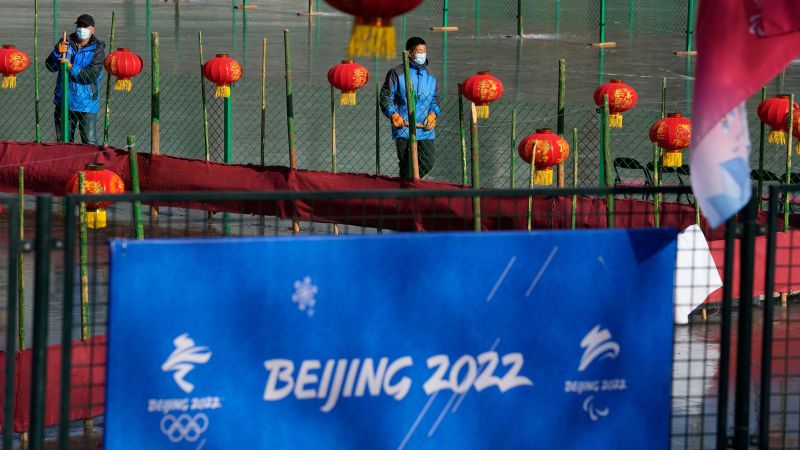

Come February, the global spotlight will again shine on Beijing – the first city to host both the Summer and Winter Olympics.

But the contrast between the two Games is stark.

Whereas the 2008 Summer Olympics was widely regarded as China’s “coming out party” on the world stage (replete with the official theme song, “Beijing Welcomes You”), the 2022 Winter Games will be held within a tightly sealed Covid-safe “bubble” isolating participants and attendees from the wider Chinese population.

As the Tokyo Summer Olympics has illustrated, pulling off a major international sporting event during a pandemic is no easy task. And for China, it is all the more difficult given its determination to eradicate the virus within its borders.

But it’s not only the coronavirus that Chinese officials will be watching out for. Athletes and other participants will be closely monitored in a bid to prevent any potentially embarrassing acts of protest against Beijing.

Activists have long called for a boycott of the Games in protest of China’s human rights abuses in Xinjiang and Tibet, as well as its political crackdown on Hong Kong. Beijing’s recent silencing of Chinese tennis star Peng Shuai’s sexual assault allegations against a former top leader has further amplified such calls.

Already, the United States and a number of allies have declared a diplomatic boycott of the Games. And although athletes from those countries will still be allowed to attend, there is a possibility, however slight, that some might feel the urge to speak out.

Having endured successive coronavirus outbreaks and costly lockdowns, questions as to the sustainability of China ambitious zero-Covid strategy remain ever present.

For now, there’s no sign that Beijing is willing to change track. If anything, efforts to stamp out the virus have only intensified in the lead-up to the Beijing Winter Olympics.

In Xi’an, an ancient city in northwest China, 13 million residents have entered their tenth day of home confinement as officials struggle to contain the country’s largest community outbreak since Wuhan, the original epicenter of the pandemic.

The lockdown is China’s strictest and largest since Wuhan, which sealed off 11 million people in early 2020.

However, local officials appeared to be ill-prepared for the tough policies they imposed. Over the past week, Chinese social media was inundated with cries for help from Xi’an residents facing shortages of food and other essential supplies, as stores were shuttered and private vehicles were banned from roads. Access to medical services was also affected, with one university student recounting her experience of getting rejected by six hospitals to treat her fever.

For many, the latest lockdown has brought back painful memories of the dark early days of the pandemic – a period blighted by chaos and frustration.

On Thursday, thousands of people bid farewell to 2021 by leaving messages on the inactive Weibo account of Li Wenliang, the Wuhan doctor who was punished by police for sounding the alarm on the coronavirus before eventually succumbing to the disease.

“Hi Doctor Li, it’s been two years, yet those overseas still cannot return home, and those at home can still face food shortages,” said one comment.

December 30, 2019, was the day Li learned of the virus and shared the information with fellow doctors. Since his death, people have regularly posted on the whistleblower’s account.

“Two years ago I didn’t take this small piece of news seriously, and even thought of it as an overreaction. I had absolutely no idea it would turn out the way it is today. Hope you rest well in Heaven, and that we will get through all this eventually.”

Throughout 2021, some had hoped China would ease its zero-tolerance approach after the Winter Olympics, but others were more pessimistic, pointing to a key meeting of the Communist Party in the fall as a potential obstruction for the government to risk any spread of the virus.

All signs point to Xi securing a historic third term in power during the ruling Communist Party’s 20th National Congress in Beijing this fall.

Xi, the most powerful Chinese leader in decades, had already abolished presidential term limits and enshrined his eponymous political ideology into the constitution. In 2021, he took a step further, with the passing of a landmark resolution placing him on the same pedestal as modern China’s founding father Mao Zedong and reformist leader Deng Xiaoping – ensuring Xi’s undisputed rule within the authoritarian, one-party state.

Since Mao and Deng, few Chinese leaders have loomed so large over the lives of 1.4 billion Chinese people.

Under Xi, the party has tightened control on all aspects of society, from art and culture to schools and businesses. It has silenced ever more critical voices in public, wiped out a growing list of China’s biggest stars, and extended its reach further into citizen’s private lives.

Meanwhile, Xi has waged an ideological war against what he calls the “infiltration” of Western values – such as democracy, press freedom and judicial independence – and fanned a strand of narrow-minded nationalism that casts suspicion and outright hostility toward the West.

But while Xi’s vision is at odds with those who grew up believing their country would become more open and connected to the world – as it had been in the decades following Deng’s “reform and opening up” policy – in the eyes of Xi and his supporters, China has never been so close to its dream of “national rejuvenation,” having amassed unprecedented military strength and economic might.

But while the Chinese economy was the first in the world to recover from the pandemic, its path ahead is looking less certain.

The new year will pose some big challenges for the world’s second-largest economy.

China is contending with a handful of headaches that could seriously weigh on growth in 2022, from repeated Covid-19 outbreaks to supply chain disruptions and an ongoing crisis in real estate.

The country is still expected to record significant growth in 2021: Many economists project growth of roughly 7.8%. But 2022 is a different story, with major banks cutting their growth forecasts to between 4.9% and 5.5%. That would be the second slowest rate of growth since 1990.

At the forefront of Xi’s mind is almost certainly a desire to keep the country running steadily ahead of his widely expected historic third term. He’s already signaled a desire to focus more on domestic issues than any grand international ambitions: Xi hasn’t left the country since the start of the pandemic, and his government has pressed ahead with its dramatic “Covid-zero” approach abandoned by much of the world.

But analysts have said Xi has to consider the outside world to an extent, given how much China still depends on international financial hubs for investment, tech and trade.

In the early days of the pandemic, Beijing had hoped to turn the global health crisis into an opportunity to brush up its image. It sent face masks and other medical resources to countries in need and pledged to make Chinese vaccines a global public good.

But things didn’t quite turn out the way Beijing wanted.

While China’s success in swiftly containing the virus has won overwhelming support at home, its international reputation has plummeted due to its initial mishandling of the Wuhan outbreak, the disinformation its diplomats and propagandists have spread abroad, its continued crackdowns on Xinjiang, Tibet and Hong Kong and increasingly assertive stance toward its neighbors.

Among the world’s most developed countries, unfavorable views of China have reached record highs, according to the Pew Research Service.

The vast majority of the 17 countries surveyed by Pew last year hold broadly negative views of China – 88% in Japan, 80% in Sweden, 78% in Australia, 77% in South Korea and 76% in the United States.

Analysts say Xi’s absence from the global stage has likely contributed to China’s isolation from the rest of the world.

And it hasn’t helped his own image either. Confidence in Xi also remains at near historic lows in most places surveyed. In all but one of the 17 countries surveyed (the exception being Singapore), majorities say they have little or no confidence in him – including half or more in Australia, France, Sweden and Canada, who say they have no confidence in him at all.

During 2021, China’s relations with the US further deteriorated, as tensions with Taiwan escalated. Under President Joe Biden, the US has sought closer ties with like-minded partners in Europe and the Indo-Pacific region to counter China’s rise. And those efforts are only likely to accelerate into the new year.

Party propagandists have repeatedly extolled Xi for bringing China “closer to the center of the world stage than it has ever been.”

But whether China wants to be there all alone is a question awaiting the party – and Xi – in 2022, and the years to come.